The transfer of power

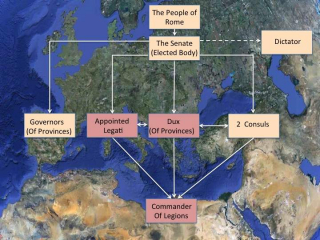

Neither the Senate, who initially had the power, nor the Emperors, who gradually acquired it wanted to acknowledge the gradual inevitable slide slide from Republic to Monarchy. In theory the Empire was still ruled by bewildering array of Magistracies such as Consul, Praetor, Tribune, Aedile,Quaestor, Military Tribune. Under the republic all these posts were elective. Under the principate they became concentrated in one person the emperor.

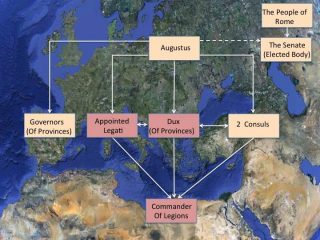

The power of the Emperor initially came from the fact that he was granted Consular and Tribuary powers by the senate for ten years Giving him total control over the city of Rome and the Armies. As well as being given the title “Augustus” i.e “Most Venerable” he was also given the title “Princeps” i.e “ First amongst senators, First amongst the people”.

The Army

Thus, although nothing seemed to have changed everything had changed. The worst effect of having no written constitution was that there was no universally accepted way for succession planning. The traditional combination of patrimony and bribery, used by the republic for senate appointments was extended and in the illusion of the continuing Republic developed a concept that the Emperor should be elected. As the Emperor was the commander of the armies, the armies came to believe that it would be they who elected the next Emperor. Events of the year of the five emporers proved once and for all that they could do this as long as they gave total support to the leader they selected. Consequently, from this point onwards the recipient of bribery was often members of the army themselves.

The legions in one part of the Empire often had a different view. The result was intermittent Civil war of various degrees of severity and appalling and totally unnecessary loss of life.

The Celts played a big part in this as the choice of emperor was made either by the eastern celts (Norica, Pannonia, Dacia, Moesia) or the western celts (Hispania, Gaul Britain. The disruption of the empire was often caused by the ambitions of rival celtic groups.

Critical Provinces

The detailed management of the provinces was at the best erratic. Each civil war resulted in a purge of officials who had supported the wrong Emporer.

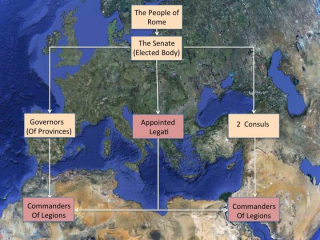

The magistracies for the “Existing Provinces” were still awarded by the senate to those of senatorial rank. The Emporer was however given direct authority over Egypt, where no one of senatorial rank was ever allowed to visit, but also Gaul, Hispania, and Syria where the same restrictions did not apply.

As the Empire expanded its boundaries Brittania, Germania and Arabia were added to these “Imperial” provinces. The public face indicated that all this was achieved apparently by case by case negotiation between the Emperor and the Senate. It was never a negotiation, the Emperor told the Senate what the outcome should be. Before long the Govenors and Magistrates of the Imperial provinces were not elected but appointed by the Emperor directly.

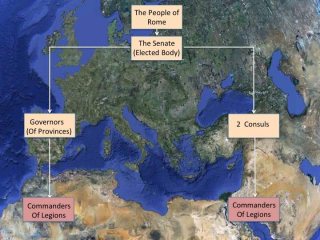

Initial structure

Expansion

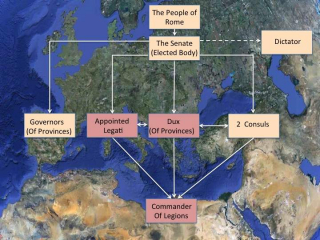

The Dictator

Augustus

From AD 217 to 284 in sixty seven years there were twenty four Emperors with an average tenure of less than two years. One tenure (Gordion) was only twenty-one days.

Fate took a hand when the emperor Carus was struck by lightening during an otherwise successful campaign against the Persians and his son Numerian died of a mystery disease on the journey back to Rome. The army chose the commander of Carus’ cavalry as the new Emporer. This was Diocles .

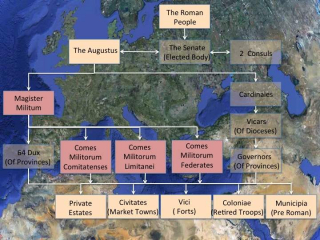

In 290 Diocletian (name change to make him sound Roman) planned substantial reforms. From now on, the provinces, almost a hundred in number, would be administered directly by the Emperor through a monarchical hierachy of “Vicars”.

Power Shift

Separation of powers

The Comes

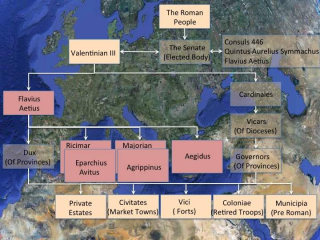

In the time of Valentinian III

Magister Militorum

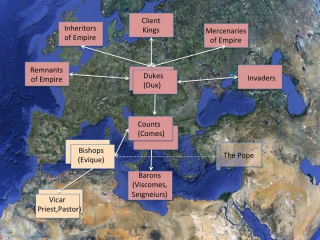

The Church

Church as Administrators

The Knights

Power Struggle