Supporting the rules

There is a prolifera of books dealing with the craft of writing. Some of the ideas in these books are widely supported and have come close to becoming standard, others are discussed vigorously, occasionally bitterly.

How have I made my selection of what was to become the basis for “my rules”?

I have read widely and have chosen a set of rules which seemed to be mutually consistent. I then revisited the texts I had used to formulate my decisions and tried to absorb as much as I could of the background thinking. In this way these authors, whom I have never met, became my mentors.

Nathan King

My real life mentor who gave me guidance and inspiration was Nathan King. Nathan King is an actor and scriptwriter based in Melbourne, Australia. He lead the course on Professional Writing and Editing which I attended. It was this course which introduced me to the work of Campbell, Vogler, Murdoch and Pearson.

Nathan gave me a basic understanding of importance of story structure and coloured it with his own experiences as well as introducing me to the sources given below. Nathan limited our studies to the three act structure but gave strong hints that we should look further.

Nathan also gave an inspiring series of lectures on ‘Myths and Symbols’, which literally changed my life, not just my writing.

Joseph Campbell

Pantheon Books IBSN 978-1-57731-593-3Joseph was a respected academic famous for surveys of different mythologies and religions.

Pantheon Books IBSN 978-1-57731-593-3Joseph was a respected academic famous for surveys of different mythologies and religions.

He came to believe that myths are created to underpin the ethos and beliefs of society, of any society. He believed that writers and artists ignore myths at their peril, as if they cut aross the more accepted myths they risk that their work will be rejected.

He concluded that the only way to undermine the validity of a myth was to create and promote another myth to succeed it.

His studies of religion convinced him that all religions are essentially the same. It is embellishments, not core beliefs which distinguish them one from another.

The two books for which he is best known; The Hero with a Thousand Faces and The Masks of God can be taken as symbolic of Campells conclusions, that both God’s and Hero’s are essentially universal, the difference lies in the presentation.

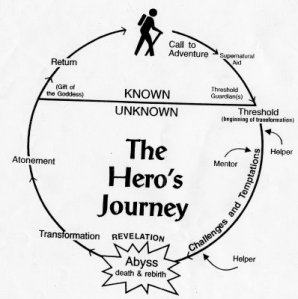

In the hero with a thousand faces he introduced the concept of the Monomyth which was picked up by George Lucas early in the development of his script for Star Wars. The Monomyth is also called “The Hero’s Journey”

Christopher Vogler

Michael Wise Productions IBSN 978-1-932907-36-0Christopher, a Hollywood story consultant, has adapted the Hero’s journey and devised perhaps the most successful attempt to integrate the steps of the hero’s journey into a traditional structure of acts, scenes and chapters.

Michael Wise Productions IBSN 978-1-932907-36-0Christopher, a Hollywood story consultant, has adapted the Hero’s journey and devised perhaps the most successful attempt to integrate the steps of the hero’s journey into a traditional structure of acts, scenes and chapters.

Vogler uses a three act structure to underpin his book ” the Writers Journey, but it soon becomes apparent that he is in fact using a four act Structure (By splitting Act 2 Into 2a and 2b)

How many acts?

Not everyone accepts all Vogler’s recomendations. Vogler suggests that the first act should end as soon as the Hero crosses the “threshold” into the new and different world, which every hero must do. Other sources, however are adamant that the first act is not complete until every major character has been introduced.

There are other similar arguments about the appropriate length for the third act and where it should commence.

Vogler introduces a linear version of the same diagram allows a proposed Tension and Crisis curve to be plotted enablling decisions such as where the main crisis occurs. The alternatives in Vogler’s text are close to the mid point of the story or well towards the end of the 3rd Act. If the objective is to consider the implications of screen writing and scripting, another version of this diagram can be used to indicate turning points and major transitions.

Maureen Murdoch

Maureen studied with Campbell but struggled with some of his concepts. At a meeting of the Atlanta Jungian Society in 2010 she identified her point of difference.

‘You always write about the Hero’s journey’ she had asked Campbell, before his death in 1987, ‘what about the Heroine’s Journey?

The answer staggered her. ‘The heroine is the object of the Hero’s Journey’, Campbell answered, adding ‘She doesn’t go anywhere, she is what the Hero is journeying to.’ It was at this point that Murdoch decided she should do some work on her own account.

The Heroines Journey

Murdoch identifies that the female version of the hero’s journey is different (and far more complex) from the male journey, mainly in that although at the start of the journey she must separate from the feminine she needs periodically to return to the feminine to restore her strength, purpose and direction. Each one of these cycles can be a journey in its own right.

The Heroines Journey therefore can become somewhat disjointed and after the requisite return to the feminine, may recommence in a slightly, sometimes totally, different direction.

Carol Pearson

Harper Collins IBSN 978-0-06-251555-1Another variant of the hero’s journey is provided by Carol Pearson. a psychologist who gained an insight into peoples behaviour and how that behaviour modifies as they develop by acting as a consultant on individual and team development to large corporations.

Harper Collins IBSN 978-0-06-251555-1Another variant of the hero’s journey is provided by Carol Pearson. a psychologist who gained an insight into peoples behaviour and how that behaviour modifies as they develop by acting as a consultant on individual and team development to large corporations.

In her book “The Hero Within” she identifies six Archetypes.

The Orphan, who feels deprived.Orphans seek to blame someone for their plight and see life as survival. They are however, as a rule, resilient.

The Innocent, who feels favoured. Innocents expect that god will give them whatever salvation they seek. They have unquenchable faith.

The Wanderer, who seeks new experiences. Wanderers feel that though their own efforts the have progressed and will continue to progress. They are very independent.

The Warrior, who sees life as a conflict. Warriors expect opposition and plan to overcome that opposition. They have a great reservoir of courage.

The Altruist, sometimes called The Martyr. Altruists expect that others will need their help and will not expect to gain personal gain from the help they give. They are capable of great compassion.

The Magician. Magicians believe themselves to be capable of altering their surroundings to meet their own needs. usually this is not illusory as they have special gifts, yielding great power.

Carol suggests that Hero’s, all Hero’s belong to one of these archetypes. however depending on circumstances the hero can migrate from one archetype to another as the story progresses and as their own character develops.

Andy Rutter

Andy Rutter is a British/Canadian multimedia designer based in Denmark. He lectures at the University College of Northern Denmark in Aalborg.

Andy Rutter is a British/Canadian multimedia designer based in Denmark. He lectures at the University College of Northern Denmark in Aalborg.

He has produced a rich website where he posts opinions, and much of his lecture topics. His true passion is video production; story telling, character development, filming techniques, editing and encoding for the web.He is also interested in the underlying theory and practice of games and gaming.

He is also a champion of the story structure described by the Freytag Pyramid and the underlying five act structure it supports. It is as a result of reading Andy’s material that I have settled on the five act structure for my writing.

Adair Jones

- The Call to Adventure

- The Road of Trials

- The Vision Quest

- The Meeting with the Goddess

- The Boon

- The Magic Flight

- The Return Threshold

- The Master of Two Worlds[6]

.

The hero’s journey is often set up as a mythological adventure that also serves as a rite of passage for the hero. There are three main parts of the journey: departure—initiation—return. Within these three parts there are a variety of stages a hero might pass through, though not all stages will be present in every story.

.

Departure

Birth Normally, unusual—sometimes quite fabulous—circumstances surround the conception, birth and childhood of the hero.

The Call to Adventure The hero lives in an ordinary world. The drama begins when he receives a call that will lead into the unknown. The hero is called to adventure by some external event or messenger and may respond to the call willingly or may be forced to accept it with suspicion and reluctance.

This first stage of the mythological journey – which we have designated the “call to adventure” – signifies that destiny has summoned the hero and transferred his spiritual center of gravity from within the pale of his society to a zone unknown. This fateful region of both treasure and danger may be variously represented: as a distant land, a forest, a kingdom underground, beneath the waves, or above the sky, a secret island, lofty mountaintop, or profound dream state; but it is always a place of strangely fluid and polymorphous beings, unimaginable torments, superhuman deeds, and impossible delight. (Campbell)

Refusal of the summons converts the adventure into its negative. Walled in boredom, hard work, or ‘culture,’ the subject loses the power of significant affirmative action and becomes a victim to be saved. (Campbell)

Supernatural Aid Once the hero has committed to the quest, consciously or unconsciously, his or her guide, often possessing magical powers, appears. More often than not, this supernatural mentor will present the hero with one or more talismans or artifacts that will aid them later in their quest.

Crossing the Threshold Upon reaching the threshold of adventure, the hero must undergo some sort of ordeal in order to pass from the everyday world into the field of adventure. This trial may be as painless as entering a dark cave or much more frightening and violent. The important feature is the contrast between the familiar world of light, where the limits of the world are known, and the dark and dangerous realm of adventure where the rules and limits are not known.

Belly of the Whale The belly of the whale represents the final separation from the hero’s known world and self. By entering this stage, the person shows willingness to undergo a metamorphosis.

.

Initiation

The Road of Trials On the road of trials, the period of initiation begins. The hero travels through the dream-like world of adventure where he must undergo a series of tests in order to begin the transformation. These trials are often violent encounters with monsters, sorcerers, warriors, or forces of nature. Each successful test further proves the hero’s ability and advances the journey toward its climax. Often the person fails one or more of these tests, which often occur in threes.

Meeting with the ‘Goddess’ This is the point when the hero experiences a love that has the power and significance of the all-powerful, all encompassing, unconditional love that a fortunate infant may experience with his or her mother. This is a very important step in the process and is often represented by the person finding the other person that he or she loves most completely. This person possesses knowledge and wisdom that will help the hero to complete the transformation.

Temptation This stage is about those temptations that may lead the hero to abandon or stray from the quest. Although Campbell refers to the tempter as a woman, temptation does not necessarily have to be represented this way. ‘Woman’ is merely a metaphor for the physical or material temptations of life, since the hero-knight of old legends was often tempted by lust from his spiritual journey.

The seeker of the life beyond life must press beyond (the woman), surpass the temptations of her call, and soar to the immaculate ether beyond. (Campbell)

Atonement In this step, the person must confront and be initiated by the force that holds the ultimate power in his or her life. In many myths and stories, this is the father, or a father figure who has life and death power. This is the center point of the journey. All the previous steps have been moving in to this place, all that follow will move out from it. Although this step is most frequently symbolized by an encounter with a male entity, it does not have to be a male; just someone or something with incredible power.

Apotheosis The hero or a stand-in for the hero is exalted to a higher rank, through a physical or metaphorical death, moving to a state of divine knowledge, love, compassion and bliss. A more mundane way of looking at this step is that it is a period of rest, peace and fulfillment before the hero begins the return.

The Ultimate Boon In this stage, the hero achieves the goal of the quest. This is the critical moment in the hero’s journey in which there is often a final battle with a monster, wizard, or warrior, which facilitates the particular resolution of the adventure. All the previous steps serve to prepare and purify the person for this step, since in many myths the boon is something transcendent like the elixir of life itself, or a plant that supplies immortality, or the Holy Grail.

.

Return

Refusal of the Return Having found bliss and enlightenment in the other world, the hero may not want to return to the ordinary world to bestow the boon onto his fellow man.

The Flight After accomplishing the mission, the hero must return to the threshold of adventure and prepare for a return to the everyday world. Sometimes the hero must escape with the boon, if it is something that the gods have been jealously guarding. It can be just as adventurous and dangerous returning from the journey as it was to go on it

Rescue from Without Just as the hero may need guides and assistants to set out on the quest, oftentimes he or she must have powerful guides and rescuers to bring them back to everyday life, especially if the person has been wounded or weakened by the experience.

Crossing of the Return Threshold The return usually takes the form of an awakening, rebirth, resurrection, or a simple emergence from a cave or forest. Sometimes the hero is pulled out of the adventure world by a force from the daylight world. The trick in returning is to retain the wisdom gained on the quest, to integrate that wisdom into a human life, and then maybe figure out how to share the wisdom with the rest of the world. This is usually extremely difficult.

Master of Two Worlds This step is usually represented by a transcendental hero like Jesus or Buddha. For a human hero, it may mean achieving a balance between the material and spiritual. The person has become comfortable and competent in both the inner and outer worlds.

Freedom to Live Mastery leads to freedom from the fear of death, which in turn is the freedom to live. This is sometimes referred to as living in the moment, neither anticipating the future nor regretting the past.