The world’s greatest forgery

The final disruption of the Roman Empire was brought about not by the barbarians but by the machinations of the Church of Rome.

The Later Roman Empire allowed great differences in culture in its many provinces Roman goverment concerned itself with revenue raising, creation and protection of trade and state security.

In about 481 Western Europe was subdivided into eight major subdivisions of the Roman Empire.

Two of these, in Britain and in the North West of the European Mainland were true remnants of the Empire.

In the South, both East and West, the Goths (Visigoths in the West, Ostrogoths in the East) ran their territories as if they were still the Empire but with a Gothic aristocracy performing the role of the Senate and government.

In the East and North East the Burgundians, Alamans and the Franks had taken contol with very different structures. They were kingdoms and their leaders called themselves Kings.

The birth of Feudalism

It was in these kingdoms that the feudal system was invented. The King assumed ownership of all land and then reallocated it to his principal supporters who often included some of those who had possessed the land before the takeover. In return for the favour of the grant of land the “Feuar” promised loyalty, financial and military support. Many of these feuars were the Comptes from the Roman era. The new arrangement in fact legitimised their position.

In all the subdivisions however, the hierachy of the Church of Rome, up to now totally separate from the state, was severely disrupted. By default local bishops aligned themselves to the local rulers for protection. Most bishops aligned themselves with Comptes. It was in this period that the tradition originated that a Compte had the right to choose the Bishop whose diocese was located within his own territory. Naturally the Compte would choose a bishop whose views, religious and otherwise, coincided most closely with his own!

This arrangement did not suit the Church of Rome as it limited the effectiveness of centralised control.

An Unholy Alliance

Clovis the teenage king of the Franks made an alliance with the Church of Rome and allowed the Church to administer civil matters.

The Church felt free to impose cultural, religious and political change on anyone who swore allegiance to the Frankish state.

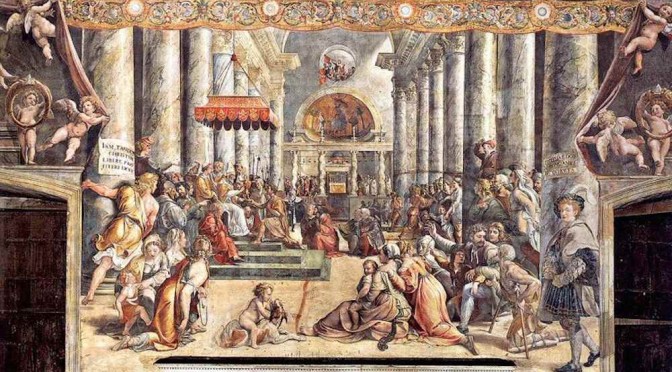

To justify what was happening, The Pope of the time developed the concept of right to rule. He maintained that Roman Emperor, Constantine the Great had given the Popes of Rome the right to the temporal rule of the Western Empire. This was ultimately supported by documentation known as the “Donation of Constantine”.

The Pope used this concept to intervene and appoint Clovis as ruler of the whole of the Western Empire. A cursory examination of the titles chosen for the new Church of Rome hierachy shows that it was the Church itself which was intended to provide the civil governance.

this was ineffect giving Clovis permission to invade and subjudgate all the other remnants of the Empire.

The Dynasty Clovis founded was known as the Merovingians.

There are many legends about why the Pope, chose Clovis, but it was really because he permitted the Church of Rome to adopt, at least in the short term, the role it had assigned to itself – to become the spiritual and temporal ruler of the Western Empire.

Clovis became the classic Client King. His job was simply to use his ruthless political and military skills to eliminate the opposition, which he did, with brutal efficiency.

Catholic Encyclopedia

The following is extracted from the Catholic Encyclopedia. Clearly there is no doubt, even in Catholic eyes, that The Donation of Constantine is a forgery .

“By this name is understood, since the end of the Middle Ages, a forged document of Emperor Constantine the Great, by which large privileges and rich possessions were conferred on the pope and the Roman Church. In the oldest known (ninth century) manuscript (Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, manuscript Latin 2777) and in many other manuscripts the document bears the title: “Constitutum domini Constantini imperatoris”. It is addressed by Constantine to Pope Sylvester I (314-35) and consists of two parts.

In the first (entitled “Confessio”) the emperor relates how he was instructed in the Christian Faith by Sylvester, makes a full profession of faith, and tells of his baptism in Rome by that pope, and how he was thereby cured of leprosy.

In the second part (the “Donatio”) Constantine is made to confer on Sylvester and his successors the following privileges and possessions: the pope, as successor of St. Peter, has the primacy over the four Patriarchs of Antioch, Alexandria, Constantinople, and Jerusalem, also over all the bishops in the world. The Lateran basilica at Rome, built by Constantine, shall surpass all churches as their head, similarly the churches of St. Peter and St. Paul shall be endowed with rich possessions. The chief Roman ecclesiastics (clerici cardinales), among whom senators may also be received, shall obtain the same honours and distinctions as the senators. Like the emperor the Roman Church shall have as functionaries cubicularii, ostiarii, and excubitores. The pope shall enjoy the same honorary rights as the emperor, among them the right to wear an imperial crown, a purple cloak and tunic, and in general all imperial insignia or signs of distinction; but as Sylvester refused to put on his head a golden crown, the emperor invested him with the high white cap (phrygium). Constantine, the document continues, rendered to the pope the service of a strator, i.e. he led the horse upon which the pope rode. Moreover, the emperor makes a present to the pope and his successors of the Lateran palace, of Rome and the provinces, districts, and towns of Italy and all the Western regions (tam palatium nostrum, ut prelatum est, quamque Romæ urbis et omnes Italiæ seu occidentalium regionum provincias loca et civitates). The document goes on to say that for himself the emperor has established in the East a new capital which bears his name, and thither he removes his government, since it is inconvenient that a secular emperor have power where God has established the residence of the head of the Christian religion. The document concludes with maledictions against all who dare to violate these donations and with the assurance that the emperor has signed them with his own hand and placed them on the tomb of St. Peter.

This document is without doubt a forgery, fabricated somewhere between the years 750 and 850. As early as the fifteenth century its falsity was known and demonstrated. Cardinal Nicholas of Cusa (De Concordantiâ Catholicâ, III, ii, in the Basle ed. of his Opera, 1565, I) spoke of it as a dictamen apocryphum. Some years later (1440) Lorenzo Valla (De falso credita et ementita Constantini donatione declamatio, Mainz, 1518) proved the forgery with certainty. Independently of both his predecessors, Reginald Pecocke, Bishop of Chichester (1450-57), reached a similar conclusion in his work, “The Repressor of over much Blaming of the Clergy”, Rolls Series, II, 351-366. Its genuinity was yet occasionally defended, and the document still further used as authentic, until Baronius in his “Annales Ecclesiastici” (ad an. 324) admitted that the “Donatio” was a forgery, whereafter it was soon universally admitted to be such. It is so clearly a fabrication that there is no reason to wonder that, with the revival of historical criticism in the fifteenth century, the true character of the document was at once recognized. The forger made use of various authorities, which Grauert and others (see below) have thoroughly investigated. The introduction and the conclusion of the document are imitated from authentic writings of the imperial period, but formulæ of other periods are also utilized.

In the “Confession” of faith the doctrine of the Holy Trinity is explained at length, afterwards the Fall of man and the Incarnation of Christ. There are also reminiscences of the decrees of the Iconoclast Synod of Constantinople (754) against the veneration of images. The narrative of the conversion and healing of the emperor is based on the apocryphal Acts of Sylvester (Acta or Gesta Sylvestri), yet all the particulars of the “Donatio” narrative do not appear in the hitherto known texts of that legend. The distinctions conferred on the pope and the cardinals of the Roman Church the forger probably invented and described according to certain contemporary rites and the court ceremonial of the Roman and the Byzantine emperors. The author also used the biographies of the popes in the Liber Pontificalis, likewise eighth-century letters of the popes, especially in his account of the imperial donations.

Doctrinal forgery?

What is very surprising is that this extract acknowledges that it was this document which formally defined the trinitarian doctrine. If it was necessary to define the doctrine in a forgery the perhaps there were other interpretations of the doctrine which did not comply with thewishes of the Church of Rome.